First Generations Speak: The Rest is Still Unwritten

By Nyles Pollonais

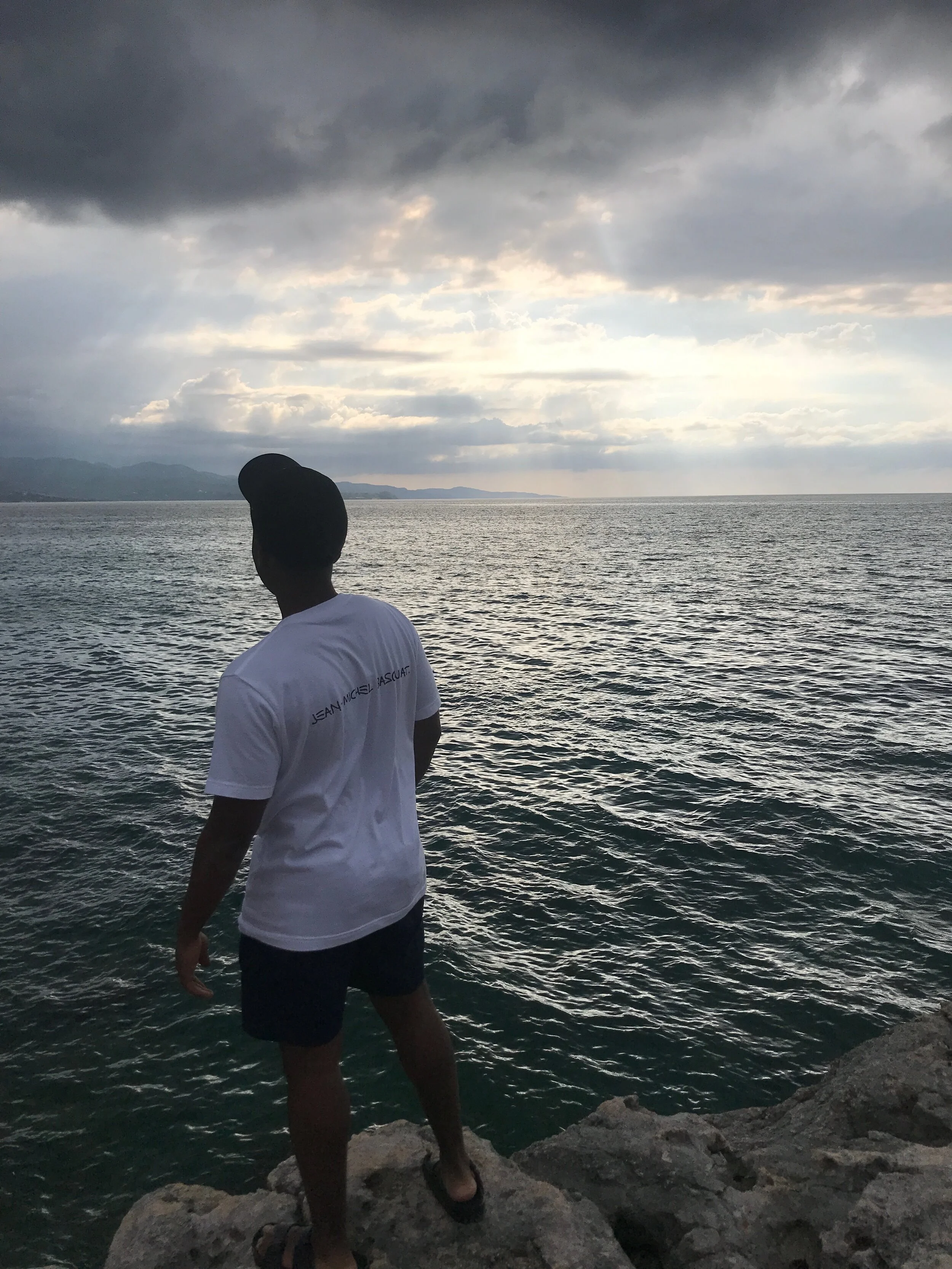

The first time I left North America was 2019 when I traveled to Jamaica for my 24th birthday. I didn’t have any family members or one of those international travel gurus to accompany me. It was just me, my younger brother, and his girlfriend. This was my first experience leaving the country. As the eldest, I did my best to take all of the precautions I could, seriously: I registered my trip with the US State Department, printed multiple copies of my passport and license, and created a detailed itinerary. I packed like I’d never return with items like ramen noodles, toilet paper, spices, a portable Wi-Fi device, and first aid supplies. I even put away my jewelry, my laptop, and my overly-friendly personality to make sure I didn't attract the wrong attention upon arrival. In the event of a natural disaster, government coup, or an unforeseen circumstance, I was determined to survive, and moreover, to prove my American identity.

Realistically, I felt torn between I know where I'm going and I'm not so sure. See, I believe there exists an internal struggle, a sort of double consciousness, in the minds of first generation Americans. Our blood, or our instinct so to speak, derives from the culture wherein we originate, but the sweat, or the nurturing, came from the society in which we were raised. This dichotomy makes one want to be fluent in both nature and nurture, but in actuality, partially literate in either. As we touched down in Sangster Intl. Airport and took our comfortable taxi to the gated AirBnb condo, I realized that there was something I hadn’t prepared for, couldn’t pack for, and definitely could not have foreseen before arriving. We stopped at our first red light on the left side of the road, I looked out of the window and saw a skeleton of a man with long silver and brown unkempt dreads, wearing barely a shred of clothing, pick up a dusty Gatorade bottle with what looked like yellow liquid. In the hot sun, he drank from the bottle like his life depended on it until violently spitting it out, and before I knew it, he kept searching the ground and we were on our way. I could not possibly have prepared for how little I would know of the world that my family left behind, and in turn, how blessed I would seem to those who didn’t have the choice to leave that very place. The dichotomy suddenly appeared.

The phrase “You don’t even know how blessed you are,” accompanied by a story detailing the struggle that the narrator, who is an immigrant and your elder, faced when they lived in the country of their birth is often used to demonstrate what the listener can not grasp about the world they currently live in. I heard it when I compared myself to others in America and upon reaching my first Caribbean country for my 24th birthday, I realized the narrators were telling the truth. Fundamentally, I did not know how blessed I was. No amount of Curry Chicken, Alison Hinds, or linguistic code switching could have prepared me for the outside world; Jamaica hit me like a ton of bricks. I immediately became invested in the relationships between citizens and government, the industries that thrived, and the everyday lives of those inhabiting Jamaica. I wanted to see if I knew what I thought I did about my West Indian heritage. I interviewed almost everyone I came across and, long story short, I learned that the government was corrupt, tourism was the largest industry, and poorer Jamaicans faced the ongoing threats of gang-violence and food insecurity on a daily basis. Like the readings my undergraduate studies described, developed nations would often exploit developing countries for their resources and time and time again, it was the people who paid the price. For the first time, I could see, and not just hear through music, the reality of the Jamaican plight.

The revelation really hit home when we checked into our AirBnb and met our host, Sarah. After touring the condo, wearing yoga pants, using a sort of British twang in her speech, and looking a bit defeated she said, “ I’d been applying to schools overseas for about 10 years and have never been successful in leaving Jamaica.” Sarah was an incredibly bright person, the same age as I, and she worked multiple jobs in the ‘Mobay’ area. I learned that access to education and opportunity was denied to many people just like Sarah. This prompted me to really understand how blessed I was to have the opportunities and access to education that I did as a first-gen in America, However, with it came the guilt, and the concern for all those people who were not afforded the same opportunities, those stuck in circumstances outside of their choosing; those who were not so lucky.

Growing up in New York City, I was blessed to be able to attend two private schools: Phyl’s Academy and St. Luke’s Catholic School. Having access to a decent education, and even the opportunity to choose your educators, are two distinct privileges of American society for which I am eternally grateful. As a young kid in New York, I did not identify exclusively through a color or race. Rather, I saw myself as an individual. I, like many of my friends and classmates, came from a complex background, but I never felt like I was anything more than human. Most of the kids at school were similar, in that we each seemed to have a stable home life, food to eat, clothes to wear, and — if we behaved— toys and video games to play with. At that time, it really felt like we had no care in the world. That is, until 9/11. That was the day I became introduced to the idea of race and heritage. I remember I was in elementary school at St. Lukes the day before my mother’s birthday.

She had dropped me off, and left to continue planning the celebration that would come the next day. Shortly after, as I recall, school had been paused for the day and all the students were to stay in their classrooms as the teacher’s listened to the announcements from the intercom and tried to find the TV that was playing the news. I remember hearing that a plane had flown into one of the Twin Towers and that they had called all of the parents to come pick up their children. Mom came back and we had to find our way back to Brooklyn. As we walked down Christopher Street, I looked up and said, “Mom, it’s another plane.” Mom kept walking, hushed me, until she looked up, and realized what had happened. Chaos ensued, but long story short, we made it home safely after walking from Manhattan to Brooklyn. From that day on, I noticed a shift in the treatment of immigrants of Middle Eastern backgrounds and people who closely resembled a person from that area.

There was even a difference between African-Americans and Caribbean-Americans. I’d always remembered hearing about the experiences my mother and her siblings faced in growing up in the New York City public school system. Those were the stories that made my mother decidedly unwilling to let her own kids grow up in that system. In Canarsie, we lived across the street from a public school, and my mother always used that particular school as a key example of why we couldn’t go.

We moved to Georgia for a few reasons: One, was to avoid the public school system in New York. Another, was because my mother had gotten a job in Florida, and she thought that my aunt’s stable home life would be better for my brother and me. So, I moved in with my cousins, who were more like my siblings at the time. This is where I was first introduced to the American public school system. Lawrenceville/Dacula was much different than Brooklyn. I immediately observed the differences between the North and the South: the country accents, the leftover taste of segregation, the warm weather and expansive landscapes, and the seemingly missing (or deliberately neglected) international populations and history — talk about an immigrant. Of course we saw others who looked like us, but the only people who knew what we were products of, were our family members. I still remember to this day, a middle school teacher of mine asking me if, “I was out of my cotton-picking mind.” I was so dumbfounded when I heard the term, because I really had to think about what he could’ve been referring to. I understood the history of slavery in the United States, but by no means did I associate myself mentally or physically with the folks who went through slavery here. The slavery in Guyana and Trinidad was an unspoken occurance, a touchy subject to this day, and outlawed years prior to the American prohibition of the system. From that day on, with many other situations like that, I kept a watchful eye for that behavior, talk, and body language. As time went on, I attended Dacula Middle School, and then Mountain View High School where I came to understand and appreciate the culture of the South and what it meant to be a Southerner, even if I did not subscribe to it. I maintained my West Indian heritage and Northerner status, like I thought I would lose it. The transition from private school to public school allowed me excel in my studies very quickly, and I soon graduated from high school with a 3.8 GPA and The Gates MIllennium Scholarship. Before I knew it, I was off to a deeper part of Georgia to attend Georgia Southern University in the fall of 2013.

I reached Georgia Southern University in August 2013, and I was off to a good start. College seemed like the 13th grade, to be quite frank, when it came to the academics. I had two roommates, both Southern guys, who were pretty cool, but you could tell they had never lived with a Black person, or a West Indian for that matter. Statesboro was nothing like Gwinnett County. As I look back, if Statesboro was Georgia, Lawrenceville/Dacula would’ve been New York. Once you left the campus, there was one mall in the area, a ‘Cookout’ — the premier fast food restaurant in the area— , and separate clubs deemed “white” or “black” by the students who would frequent on the weekends. After 2 months in that semester, I had enough, and the one racist experience I faced in October forced me to get the hell out of that area.

I applied to New York University as a transfer student at the end of that first semester and never looked back. In January 2014 I reached NYU, my mother’s alma mater. Initially, I thought I knew what I was doing. I’d guided my steps with the memories I had of the city as a child, but this place was nothing like I remembered it. Coming to New York City instead of Brooklyn this time from Georgia was like moving into another country all over again. The culture shocked me at first: the amount of wealth displayed effortlessly, the return to rigorous academic study and expectation, and the profound need to show authenticity was the challenge I was ready to face, or so I thought. I came to terms with what I knew about my own West Indian culture by meeting up with old friends, visiting family members, and by visiting clubs. I changed my view on sexuality as I got to know my first roommate and his friends, the first people to welcome me into their social circles. What I thought about LGBTQ+ people was challenged by the experiences I had. It helped me to understand my own sexuality, the fluidity of sexuality, and the spectrum in which we all live. I came to terms with the academics, as well. Just as going to Georgia helped me to succeed in my academics, coming back to New York forced me to step up my game to a new level. No longer did I have that edge; I had to put in the time and effort to regain my balance. These experiences, I figured, was what it must have been like to be an immigrant anywhere.

I graduated in December 2017, as the first grandchild of both my maternal and paternal grandparents, and eldest son of Michelle Williams and Nigel Pollonais to achieve his Bachelor’s from a university in the United States. Most recently, I co-founded BinaryAeon.com, a cyber-security company focused on democratizing online data, with a friend from NYU who is also the son of immigrants. It wasn’t always easy, but I had to remember my foundation and the reasons why I did what I did, and do what I do. Reaching Jamaica for my 24th birthday helped me to understand and contextualize the blessings I received living here in America.

The immigrant story is not a historical anecdote that we can simply look at like it just happened once. It is an ongoing story of migration around the world, to and fro. People who come to America or any other country than their birth, for that matter, are just like people everywhere else. We are human at the end of the day. We are motivated by the same need to belong and the drive to succeed. Too often, immigrants are not viewed as people and instead leeches who don’t have anything to return to society, but I hope that my story can change that narrative one day. I am the child of immigrants who have given their all to their communities and children. Until the final article in this series, as my maternal great grandmother would say, “Trust to see you soon.”

Meet the Writer

Nyles Pollonais graduated from New York University in 2018 with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. He is a writer, entrepreneur, musician, and future educator who spends most of his time focusing on political theory and current events. He encourages you to take a look at his company, Binary Aeon, and the work they're doing to protect individual data rights and online privacy.